1777 Battle of Germantown

History of the Battle of Germantown

Benjamin Chew was not in Pennsylvania during the Battle of Germantown. As a supporter of the proprietary rights of the Penn family he was held in suspicion by the American patriots, but was not considered a loyalist Tory. Initially, the American government planned to confine Benjamin at Cliveden, but after several different sites were proposed, Chew and Governor John Penn finally were exiled and held under house arrest at Union Forge, Joseph Turner's iron works in Hunterdon County, New Jersey.

In late September of 1777, after victorious encounters with American troops at Brandywine and Paoli, British soldiers occupied Philadelphia, then the capital of the Revolutionary government. The occupying army quartered several thousand troops in the nearby village of Germantown, about 6 miles northwest of the city.

In late September of 1777, after victorious encounters with American troops at Brandywine and Paoli, British soldiers occupied Philadelphia, then the capital of the Revolutionary government. The occupying army quartered several thousand troops in the nearby village of Germantown, about 6 miles northwest of the city.

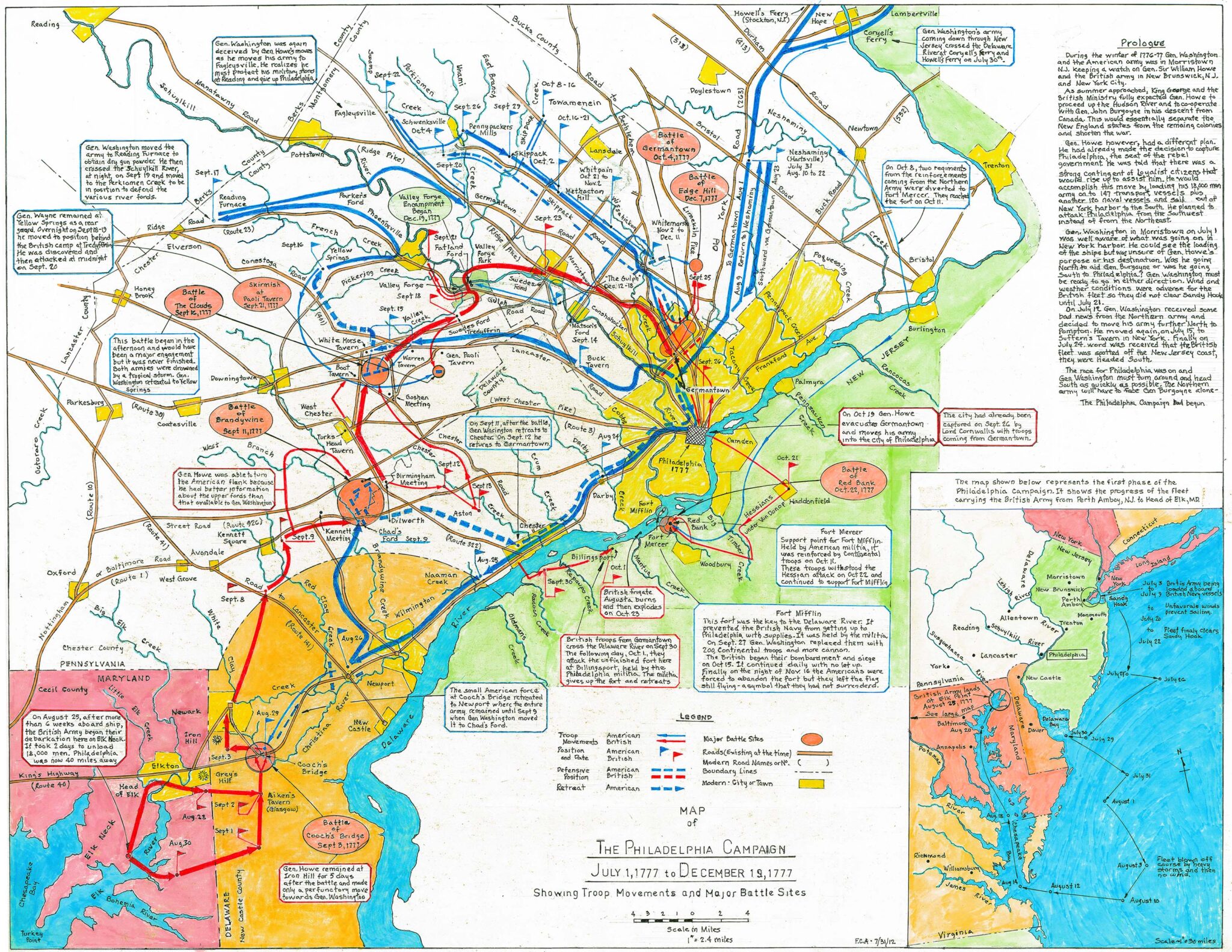

In early October, from his headquarters in Skippack (Montgomery County), General George Washington plotted to recapture the capital as quickly as possible. His elaborate battle plan called for an assault on Philadelphia from the northwest, aimed through the heart of Germantown. Overnight and through the early morning hours of October 4, as many as twelve thousand men moved south towards Germantown by several different routes, hoping to catch the British by surprise. Washington himself was with the column attacking on the Germantown Road through Chestnut Hill and Mt. Airy.

Advancing Americans on the Germantown Road encountered a British picket outpost near, what is now, Allens Lane in Mount Airy. The resulting burst of artillery fire from nearby alarm cannons alerted British Colonel Thomas Musgrave’s 40th Regiment, which had camped in the fields around Cliveden.

As the pickets fell back to join Musgrave's 40th Regiment at the house, the American advance unit followed, rushing past Cliveden in the fog. Colonel Musgrave, realizing that his troops were cut off from the main British line, ordered some of his men into the mansion. Closing the first floor shutters and barricading the doors, he posted marksmen at the windows on the second and third floors. Musgrave’s men had time to barricade themselves inside the thick stone walls of Cliveden and turn it into an impregnable fortress from which they could fire on the advancing Americans with impunity. The pursuing Americans soon realized that they were between Musgrave's companies at Cliveden and the main British forces near Market Square. Fearing that they would be cut off from support, the Americans fell back towards the main body of their column. General Henry Knox was reluctant to leave such a fortress as Cliveden in British hands, so he advised Washington that the Americans “reduce” the mansion. In the ensuing battle, neither American cannon nor efforts to burn and storm the house were successful.

After several hours of intense fighting in and around Cliveden the Americans retreated back into Montgomery County, and eventually to a long winter at Valley Forge. They left behind more than 152 dead soldiers in Germantown, 70 of them on the grounds of Cliveden. British casualties were less severe, but a visitor after the battle described the interior of Cliveden as looking “like a slaughterhouse.”

Consequences & Aftermath

The intricate choreography of Washington’s plan was spoiled by the combination of unexpected British opposition and characteristic autumn weather - heavy fog shrouded most of the area during the morning. Washington’s column, stalled in front of Cliveden by heavy fire from inside the house, was unable to rendezvous as intended with the other segments of his army at Germantown’s Market Square. In fact, the confusion was so great that at one point two American units were firing on each other. The Americans lost the battle, but the combination of the valiant effort at Germantown and a victory at Saratoga secured French support for the American cause.

Benjamin decided to maintain a low political profile for the duration of the American Revolution, thus avoiding the perception of his possible support for the British. In the fall of 1779 he rented his town house on 3rd Street, sold Cliveden to Blair McClenachan and went into self-imposed exile with his family to "Whitehall," the family plantation near Dover, Delaware.

Honoring this significant moment in Philadelphia history dates back to a Centennial Celebration held at Cliveden in 1877. Today, the Revolutionary Germantown Festival keeps the tradition alive, energizing the community with a day of family entertainment and Battle of Germantown reenactments. Join in the festivities every year on the first Saturday of October.

Considering Re-enactments

In 2020, Cliveden along with our local community and the re-enactor community collaborated to discuss the site's interpretation of the American Revolution and the Battle of Germantown as the city and nation grappled with an increase of gun violence. Programming included Cliveden Conversations and roundtables with stakeholders to gain new perspectives on how best to tell the diverse stories of the revolution and also meeting the needs of our community. To learn more about the project, click the buttons below.

Save the Date!

The Revolutionary Germantown Festival returns Oct. 5th to commemorate Germantown's revolutionary history.