Popular culture would have us believe that wills – the documents that specify what will happen to our property when we die – are things to be feared or avoided until we are forced to face their necessity. But, genealogically-speaking, wills and other estate records can be pure gold, especially when trying to trace the lives of the enslaved. Because these human beings were considered chattel property, they – our ancestors and community members – were enumerated in wills and estate records just as was household furniture and farm implements. The inhumanity of this is painful to see, but on a logistical level, these documents tell us where our family and community members went – or at least where they were supposed to - when their owners passed away.

There are at least 4 sets of wills, estate inventories, and/or other estate documents in the papers that have been digitizes as part of the Illuminating Hidden Lives project: Benjamin Chew’s [ID: 18274, 18276], Samuel Chew [ID: 18444, 19146, 19158], Mary Chew [ID: 18334], Joseph Turner [ID: 18296, 18311, 18308]. This list of IDs is not exhaustive – interested researchers should do a full search on HSP’s Omeka site for all related documents in each case.

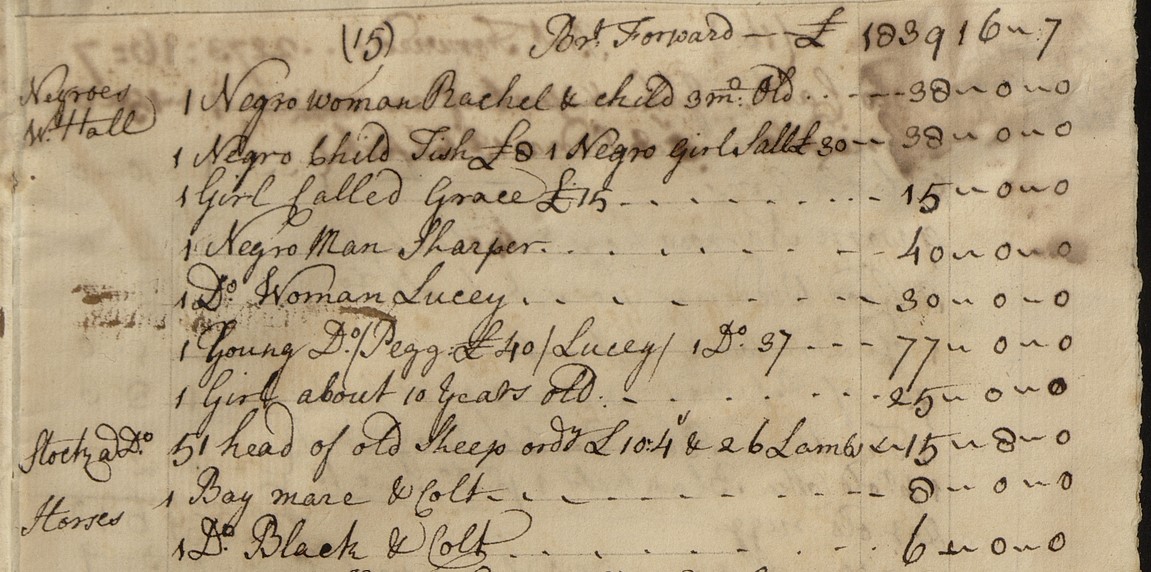

These documents provide a treasure trove of information about the enslaved families and communities owned by the Chews, and raise questions as well. Thanks to some of the documents, we know who was where and when, though imperfectly. Sometimes parents were named, but their children were not, as in Mary Chew’s records [18334]:

This is a partial list of “Negroes at White Hall,” one of Mary Chew’s properties. Who is Rachel’s 3-month-old child?

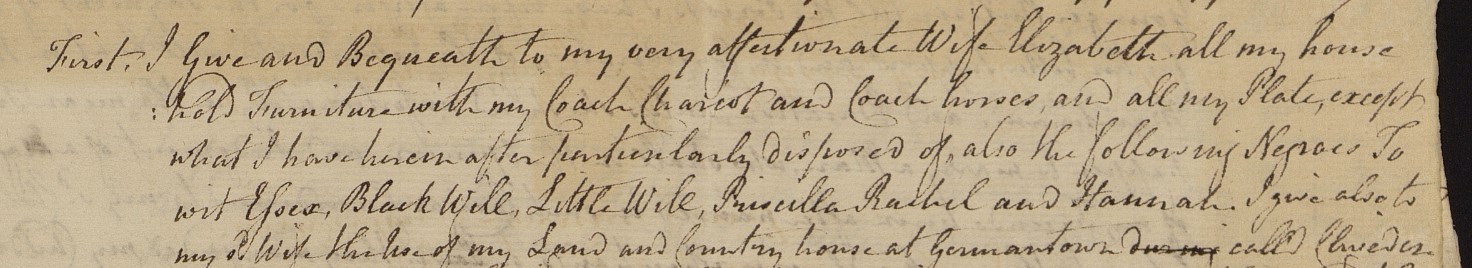

Sometimes, there were disappearing individuals. Between 1770 and 1781, Benjamin Chew drafted and redrafted at least 3 versions of his will: one in 1770, another in 1777, and a third in 1781. Each document names a slightly different grouping of enslaved individuals. In 1770 [ID: 18274], named are Essex, Black Will, Little Will, Priscilla, Rachel, Hannah, Jenny, George,

and Dinah. In 1777, Essex, Hannah, Jenny, and Dinah are missing from the list. In 1781, only Rachel and George are listed explicitly. Why? Cross-referencing these drafts with other documents might provide the answer.

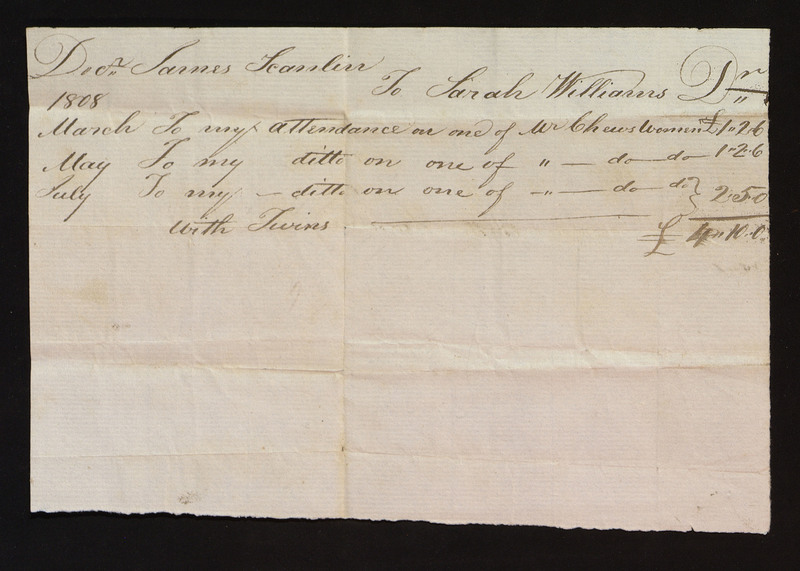

By far, one of our most exciting finds was this: the names and mother of a set of twins who had been delivered in July 1808. Somewhere part-way through our first round of document exploration, we came across a bill (or maybe simply a scrap record) showing that 3 women had received medical visits – seemingly for childbirth – between March and July of 1808 [ID: 18387]. Unlike some other records in the larger Chew Family Papers set, none of the three women were named. But one of the women had given birth to twins. Who were the mother and children?

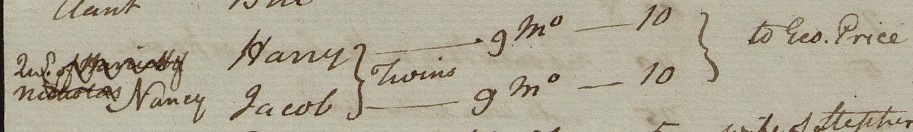

Towards the end of round 1, we decided to tackle a large file within the record set: records from Samuel Chew’s estate [ID: 18444]. It’s a 31-page PDF – so large it couldn’t be made available as individual images within the Omeka system. But it was so worth the time it took to go through! Not only were there lists of enslaved people broken down by each of Samuel Chew’s properties, these lists showed who was purchased by whom and for how much, and one incredible set of lists noted who were the children of each woman. That included the following notation:

It reads “Nancy” in the column for “Child of” and the names “Harry” and “Jacob,” each “9 mos” (9 months) in the columns for the names and ages of the primary individuals. Given that Samuel Chew passed in March 1809 and his state began to be administered soon after, it seems almost certain that the twins born in July 1808 are none other than those 9-month-old twins, Harry and Jacob, who are the children of Nancy on the “Great Plantation.” How cool to make that connection, especially given that it is almost certain no other birth record was created for those children.

There is so much information to be found in the wills, will draft, estate inventories, and other estate documents in the Chew Family Papers, and so many more questions to be asked. Take some time to explore, or take a deeper dive, by visiting https://omeka.hsp.org/s/digitalcollections/page/Illuminating-Hidden-Lives. Try using “Estate” as a starting search term.

Upcoming Post

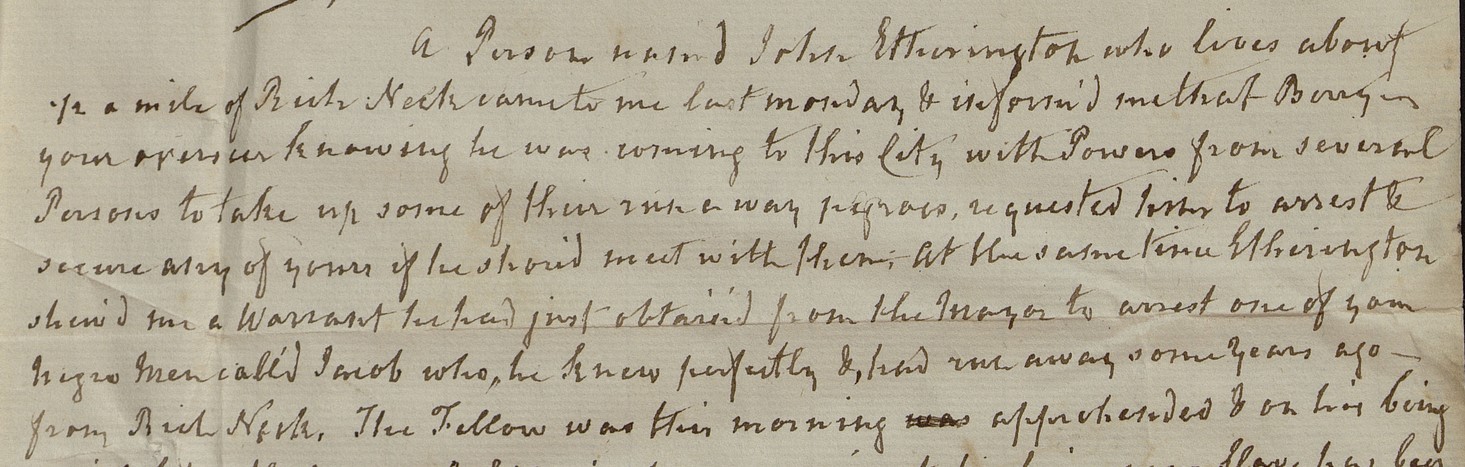

While working with the Chew Family Papers, the AAGG discovered information about enslaved people seeking their freedom. One enslaved person who was repeatedly mentioned was a man named Jacob, who in 1803 was seeking his freedom from Samuel Chew, the half brother of Cliveden's owner, Benjamin Chew, Sr.

Illuminating Hidden Lives: Black Stories of the Mid-Atlantic Region was funded by the National Trust for Historic Preservation's Interpretation and Education Endowed Fund that was made possible by a challenge grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Learn more about Illuminating Hidden Lives!

Click the button below to learn about and watch program recordings for our current project with the African American Genealogy Group and the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.