Slavery and Servitude

The institution of slavery is woven deep into the economic growth and political fabric of America.

Book Marks

Benjamin Chew was born on a Maryland plantation into a family with a history of slave-holding dating back to the 17th century. Benjamin was the patriarch of one of the largest and latest slave-holding families in Philadelphia.

Enslavement

The Chews’ ambivalence toward enslaved peoples can be found in the Chew papers. The enslaved were considered primarily to be property, but were also seen as people, albeit a lowlier race fit only for enslavement. Some Americans, like Benjamin Chew Jr., felt that the enslaved were better off in bondage than free.

“Will, I hear, has made his escape to some other country but the hardship he must experience from a different way of living than that in your employ will sufficiently punish his ingratitude.” – Benjamin Chew II (1778)

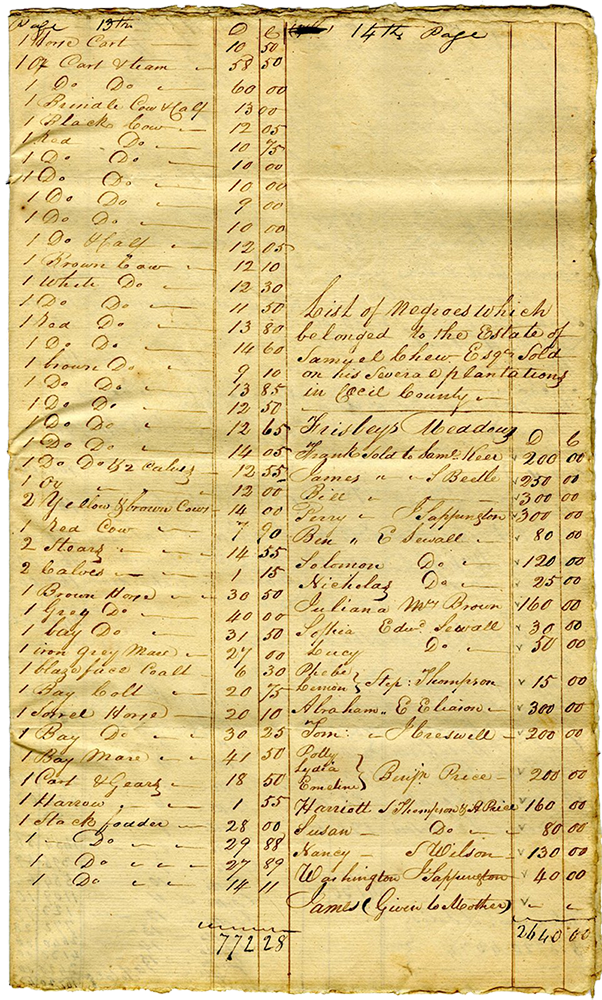

Much of the Chew family wealth created and sustained during the 18th and 19th centuries was founded on investments directly or indirectly connected to slavery. The financial ability of Dr. Samuel Chew to send his son Benjamin to law school in London was built, in part, on the labors of the one hundred and forty enslaved Africans he owned. Benjamin Chew would go on to acquire a total of nine plantations in Maryland and the Lower Three Counties, which is modern day Delaware. At the Chews’ Whitehall Plantation in Delaware, the Chew papers have uncovered sixty years of information about enslaved Africans. The lives, families, and resistance to authority of those enslaved on plantations owned by the Chews can be seen through the papers.

Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church and its first Bishop, wrote in the first sentence of his autobiography that he was born enslaved to Benjamin Chew. The Chew papers contain letters written by enslaved Africans that give a more detailed description of the hardships and heartaches they endured. Many of the enslaved people on Chew’s plantations can now be identified by name, location, and year of birth because of the Chew papers. The Chew family held enslaved Africans in the city of Philadelphia and in Germantown during the 18th and 19th centuries. Urban slavery offered the enslaved an environment where they could learn from, socialize, and worship with free Blacks as well as Whites. At any given time there were enslaved Africans working next to free Blacks and European immigrants at Cliveden. The enslaved in urban areas were used as domestic servants, trained as artisans, and even employed.

Indentured Servitude

“All importations of white Servants is ruined … and we must make more general use of Slaves.” – Philadelphia merchant (1756)

Indentured servitude differed from slavery in that it was a form of debt bondage, meaning it was an agreed upon term of unpaid labor that usually paid off the costs of the servant’s immigration to America. Indentured servants were not paid wages but they were generally housed, clothed, and fed.

The rights to the individual’s labor could be bought and sold, but the servants themselves were not considered property and were free upon the end of their indenture (usually a period of five to seven years). Nevertheless, indentured servants, along with normal servants, were often subject to physical abuse. They had to have their master’s permission to marry and found that the courts enforced their agreements if they tried to avoid all or part of their indenture.

Indentured servitude was enormously common in colonial America. In the 17th century, nearly two thirds of British settlers were indentured servants while eighty percent of European immigrants to America were “redemptioners” (immigrants who needed to indenture themselves to pay for their immigration upon arrival to the colonies, rather than ones who worked out their contracts prior to departure). Most redemptioners came from Britain or Germany and were imported to Philadelphia. The majority were young, under twenty, and died before their contracts were up due to the rough conditions of travel and colonial life.

During the 18th century, indentured contracts became less necessary as the costs of immigration to America went down and African slave labor became increasingly attractive to the large landowners of the prospering colonies. During the Revolution, indentured “imports” basically ceased and the decline continued after the formation of the United States.

Prior to this decline, Benjamin Chew’s household included indentured servants.

Paid Staff

Domestic servants generally worked long hours, seven days a week, for relatively modest wages. Their work was physically demanding. They were clothed, fed, and housed, but had little privacy. Whatever social life they enjoyed in town was limited in the country. The particular duties of each category of domestics (cook, maid, waiter, attendant, wash woman, nurse) and those who worked outside (gardener and coachman) were fairly straightforward. Those working in the public areas of the house were expected to complete their tasks without disrupting family activities. Casual workers were hired as needed.

Most of the domestics at Cliveden during the 19th century were Irish immigrant women. Irish immigrants were generally the poorest immigrants who came to America, driven by the potato famine and land scarcity in Ireland due to English policies. Irish women immigrated just as much as their male counterparts, uncommon in immigration patterns, and often worked as servants to wealthy Americans.