The Chew Family

The Chew family came to America in 1622 when John Chew immigrated to Jamestown from England.

Book Marks

Subsequent generations of the family found economic success on a variety of paths, such as legal, agricultural, and commercial enterprises in colonies of the mid-Atlantic and South. Cliveden presents evidence of the wealth, influence, life of privilege and the sense of style embraced by the Chews. As an historic site, it explores the human stories involved in maintaining such a lifestyle often on the backs of enslaved and indentured servants.

Benjamin Chew

Benjamin Chew became associated with the William Penn family in the early 1730s and later served as its representative in legal matters for the “Three Lower Counties,” now Delaware. With the Penn family’s encouragement and support, young Benjamin Chew moved to Philadelphia around 1736 to begin his study of the law, the first step in a promising political career.

An 18th Century legal education consisted of several years of study with an established local attorney and formal training in England. Chew was fortunate to be apprenticed to Andrew Hamilton, the preeminent attorney of his generation, and read law with him until Hamilton’s death in August 1741. Chew left for London in June 1743 to complete his legal education and that October he entered Middle Temple of the Inns of Court, the finest British law school of the day. He read law for less than a year before his father’s death in June 1744 forced his return to America to settle the estate.

Benjamin Chew’s father, Samuel Chew, was born a Quaker, but was read out of meeting for supporting the French and Indian War; thereafter Chew practiced in the Episcopalian church in Philadelphia (and Benjamin Chew is buried in the churchyard of St. Peter’s in Old City). Chew was married twice: first to his cousin Mary Galloway in 1747 and two years after her death he married Elizabeth Oswald in 1757, the niece and heir of Joseph Turner, a prominent Philadelphia merchant. Turner, essentially a Chew family patron, gave Benjamin the statues for the grounds at Cliveden and it was at Turner’s iron forge in Union Forge, New Jersey, that Chew and John Penn were held under house arrest during the Battle of Germantown. A painting of Turner hangs in the Front Hall at Cliveden.

Rise to Wealth

Chew rose to the position of Chief Justice of the Province of Pennsylvania before the Revolution and, after a period of political exile during the war, was reappointed to the Pennsylvania bench in the Federal era as the President of the High Court of Errors and Appeals. Chew’s political career and social prominence in Philadelphia were linked to his personal ties with the Penn family. He served as the Penn’s representative to the commissions resolving the boundary disputes between Pennsylvania and Maryland (1751) and Pennsylvania and Connecticut (1754).

Like many other wealthy Philadelphians, Chew had extensive property holdings in the city, speculative real estate in western Pennsylvania, and inherited land in Delaware and New Jersey. Many of his properties (as many as 9 of them) were plantations, where the wealth was produced by enslaved workers. His political position, his personal wealth, and two advantageous marriages contributed to his high status in Philadelphia society and by 1762 Benjamin Chew had achieved social prominence in the city.

Cliveden Purchase

After the Battle of Germantown in 1777, Chew sold Cliveden, only to repurchase it in 1797. The family used the house extensively as a summer retreat, even using it as a full-time residence from time to time. Chew’s son, Benjamin Chew, Jr. entertained the Marquis de Lafayette at Cliveden in July 1825, the first time any house in Germantown was opened to the public as a museum. The family’s wealth and influence continued the elder Chew’s pattern of shrewd capitalism and strategic marriages, and extended throughout the Mid-Atlantic region.

Implications of Wealth

The full implications of the family’s role in the Mid-Atlantic economy over the centuries are being researched in the Chew Papers. The Chew Family Papers provide tantalizing insights into the lives of the enslaved and what they did to find freedom in a slave-based plantation economy that extended into Maryland and Delaware. The records indicate examples of the Chews’ wide-ranging interests, including involvement in the opium trade in China, investments in model textile towns in New Jersey, and philanthropy for women’s education in Philadelphia. Women of the Chew family attended Queen Victoria’s wedding in 1840 and were instrumental in saving Philadelphia’s Independence Hall in the 1870s.

Modernizing Cliveden and the 1970 Fire

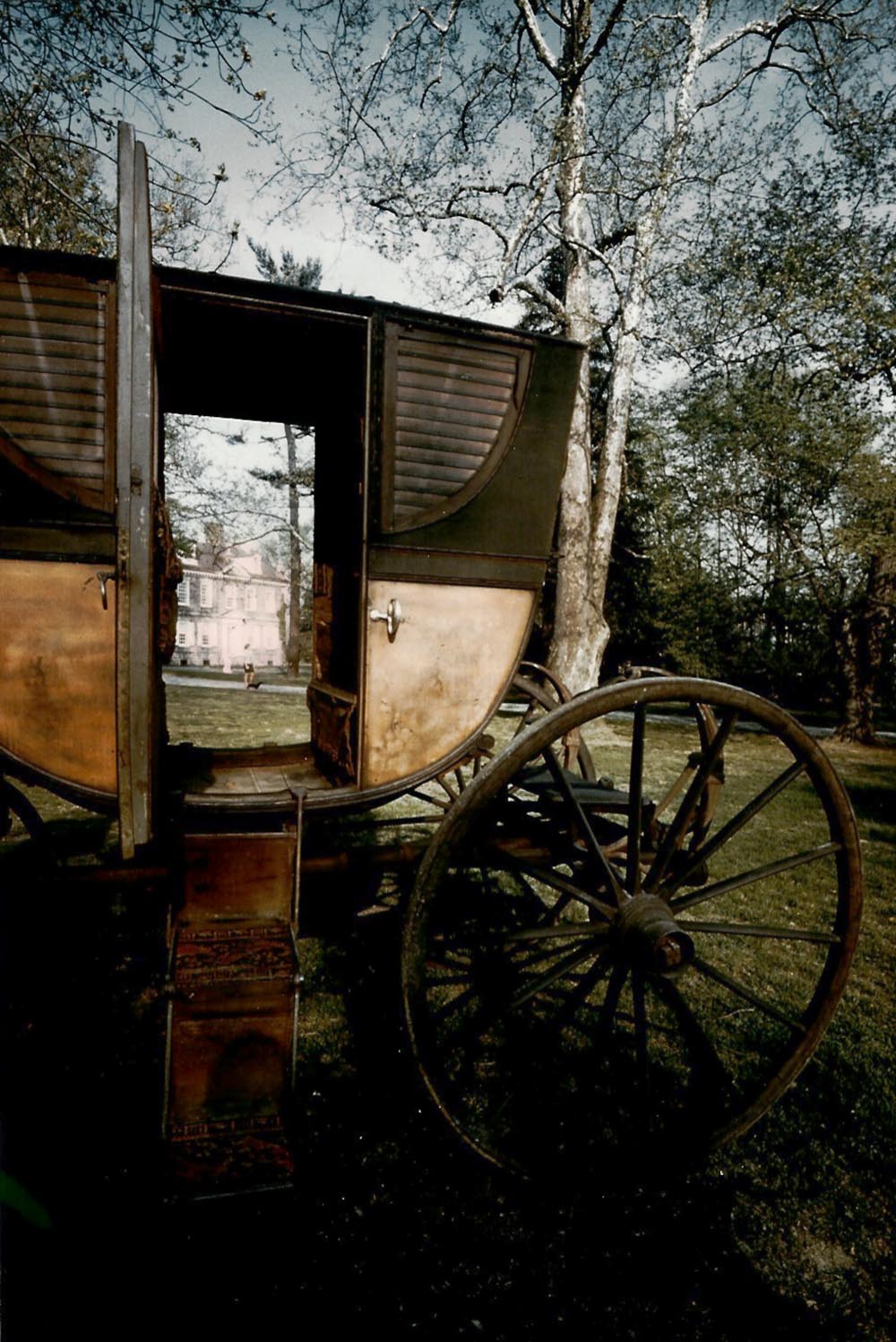

In the 20th century, the family converted Cliveden and its Carriage House to include more modern amenities, such as turning the old barn into an advertising agency. Caretakers used the old kitchen and wash house dependencies for apartments while providing services for the family. Increasingly, though, the family moved away from Germantown. An arson fire in 1970 burned the Carriage House, prompting Sam Chew to turn the entire property over to the National Trust for Historic Preservation.

While Benjamin Chew’s carriage and other important artifacts may have been lost in the fire, the voluminous documents of the family were not. They were turned over to the Historical Society of Pennsylvania in 1982, where they remain to offer all generations an opportunity to interpret the relevance of Cliveden and the Chew legacy.