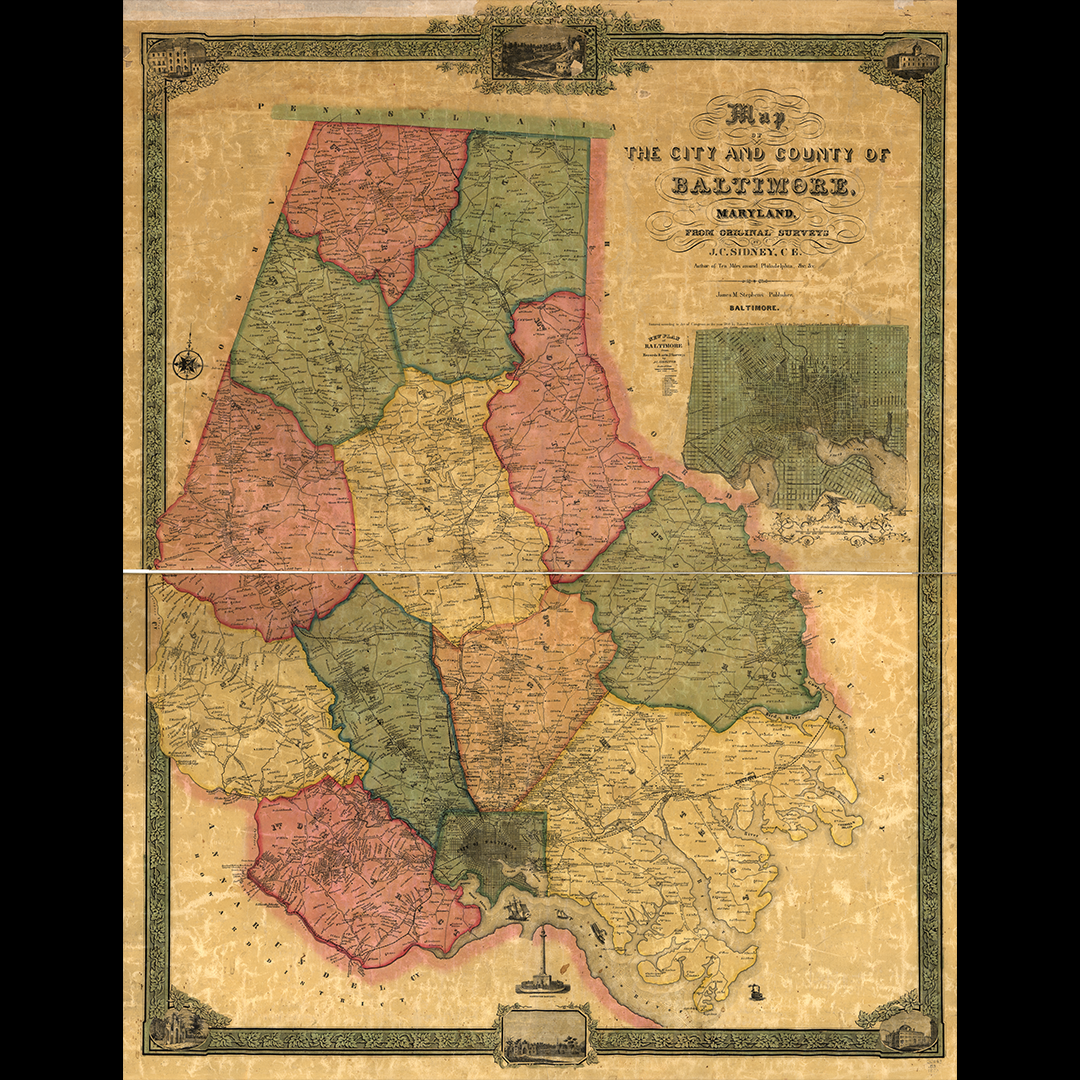

The African American Experience at Epsom Farm

Epsom Farm was a place of bondage and labor for generations of enslaved and free African American workers. When Charles Carnan Ridgely died in 1829, around 600 acres of land including Epsom passed to his youngest daughter, Harriet (1802-1835) and her husband Henry Banning Chew (1800-1866). Henry, followed by his eldest son Charles Ridgely Chew (1827-1876), lived on the property until the late 1880s when the family moved to a home in Towson.

In the 19th century, Epsom was one of the largest farms in the region. Agricultural production included cultivation of cereal crops, hay, fruits and vegetables, production of dairy products and livestock. Over 27 enslaved people toiled at Epsom along with freed African Americans and white German workers.

After the Chew family moved to Towson, Epsom was leased to tenant farmers. In 1894, the Epsom Mansion burnt to the ground. The land continued to be farmed into the 20th century and in 1921 the Chew family sold the land to Goucher College.

Enslaved & Free Black Workers

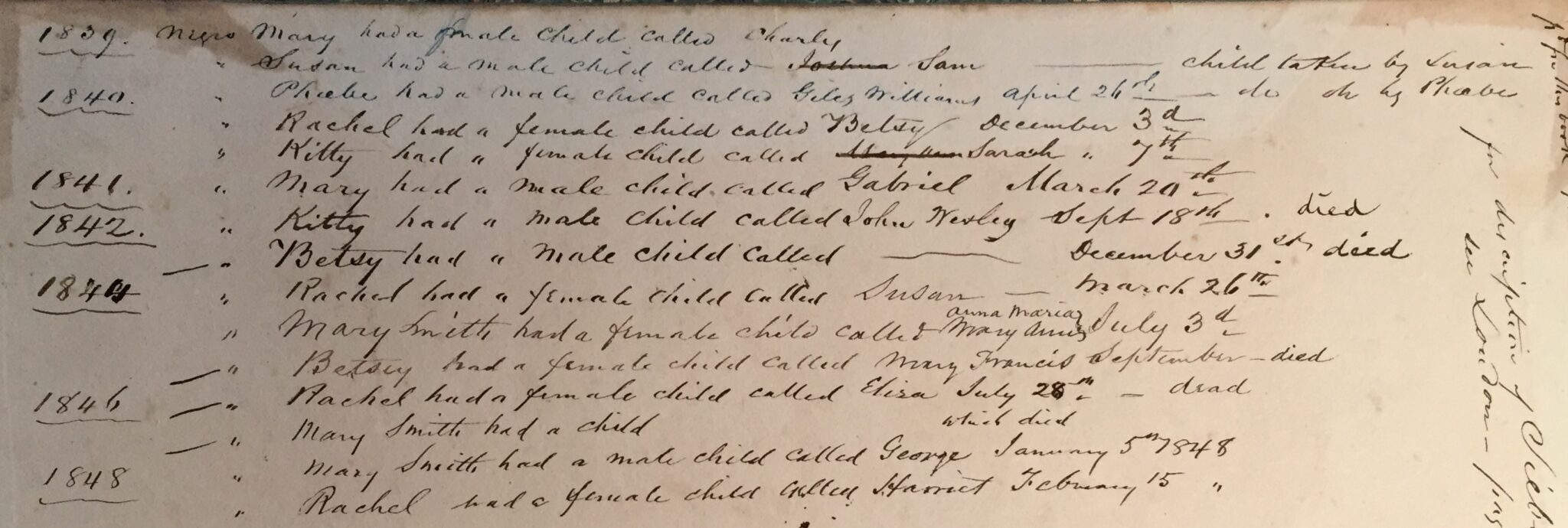

Under the terms of his will, Governor Charles Carnan Ridgley bequeathed 19 enslaved people to Harriet Ridgley Chew and her husband Henry Banning Chew. The enslaved individuals were to be manumitted once they reached the age of 25 for women and 28 for men. Chew purchased and temporarily hired additional enslaved labor to meet his needs over the next 30 years. Cash books, memoranda of field work and journals of farm expenses document the lives and work of people enslaved at Epsom Farm.

For newly freed men and women, work at Epsom Farm was an opportunity to earn wages and allowed freed workers to remain close to family members who were still enslaved. Chew hired free black workers to perform farm labor, dairy work, blacksmithing, shoemaking, coach driving and gardening. Male farm hands or hirelings started at $6 to $8 per month. Skilled free black workers in some cases earned as much or even more than free white workers at Epsom Farm.

Kitty Barton (born c. 1823)

Kitty came to Epsom Farm from Hampton as a child under the terms of the Ridgley will. Chew attempted to sell Kitty together with her two young children, Sarah and John Wesley, in an 1844 advertisement for a cook in The Baltimore Sun. Kitty and her children were not sold and remained in bondage at Epsom Farm. After Kitty's manumission in 1848, she continued to labor on the property for wages of $5 per month through the mid-1850s.

Family Life & Resistance

For enslaved African American families, slavery was a cycle of continuous displacement and loss. Enslaved workers at Epsom Farm were separated from their families at Hampton and other nearby plantations. The practice of gradual manumission continued to separate families as people were freed and others remained in bondage.

Mary Smith (born c. 1826)

Mary was taken to Epsom Farm in 1835 at the age of nine with another woman, Phoebe Blackson, aged 18. She gave birth to three children at Epsom Farm: Anna Maria or Mary Ann, George, and an unknown child who did not survive. Mary was manumitted in 1851.

Phoebe Blackson (born c. 1817)

Phoebe was enslaved at Ridgley's Forge until 1835 before her transfer to Epsom Farm. Phoebe gave birth to triplets on December 23, 1835: Jacob, Isaac, and Abraham. By February 24, 1836, all three children died. In October 1836, Phoebe married Lewis, a free black man who worked for wages at Epsom Farm after his manumission. In 1840, Phoebe gave birth to a son, Giles Williams. In 1842, at age 25, Phoebe was manumitted, and in that year she took her two year old son, Giles, with her to freedom.

Enslaved people in Henry Banning Chew's orbit regularly resisted slavery. Expressions of resistance at Epsom Farm emerge from Chew's entries in his account and memoranda books with enslaved absent from assigned tasks or noted as "run away." From the 1830s through the 1850s, Henry and his son Charles Ridgley Chew advertised in local newspapers for enslaved men named John, Shade Brown and Dick Johnson.

Shade Brown (Birth date unknown)

Frequently listed as ill or "gone" in documents, Shade practiced 'petit marronage,' repeated short instances of running away, through the first half of 1831. On July 1, 1831 he was sold to Austin Woolfolk, an infamous slave trader in Baltimore, by Charles Carnan.

John (Fisher - born c. 1819)

John escaped from Epsom Farm in November 1840. There is no record of his return. Other members of John's family were enslaved to the Ridgleys and the Chews.

Learn more about our history!

Visit our Research page for links to primary source documents, secondary sources, and connected historic sites and organizations.